Regulating Fairness or Policing Identity? DSD Rules and the Future of African Athletics

Sex classification in sports has long been framed as a biological issue, but its enforcement through Differences in Sexual Development (DSD) regulations reveals a deeper entanglement with social constructs of gender, identity, and race. While World Athletics and other sports governing bodies argue that testosterone-based regulations ensure fairness in competition, the impact has disproportionately fallen on African athletes, forcing them to either undergo medical interventions or shift to less familiar events. This article examines the science and the social constructs behind sex categorization in sports, explores how DSD regulations extend beyond track and field, and questions whether these rules truly uphold fairness—or merely reinforce an exclusionary system.

Sex: Scientific and Social Perspectives in Sport

Traditionally, sports have relied on two strict categories—“male” and “female”—assuming neat divisions based on biology alone. Yet science tells us sex is more complex. Hormones, chromosomes, and anatomy don’t always line up in a way that fits the binary model. Athletes with DSD (sometimes called “hyperandrogenic”) naturally produce higher levels of testosterone than most women.

Even so, these scientific markers don’t tell the whole story. Gender also has social and cultural dimensions, shaped by expectations about how women “should” look, dress, or perform. When institutions try to regulate “acceptable” hormone levels, they’re enforcing not just medical guidelines but also social ideas of womanhood. This duality—where science meets cultural norms—lies at the heart of the current controversy.

This article discusses athletes who have been assigned females at birth but who now have to deal with regulations which have the effect of excluding them from women’s sports. It must also be pointed out that this article does not focus on transgender athletes or regulations surrounding their participation in women’s sports as those are regulated separately.

The Testosterone Question

When most people think of testosterone, they imagine it as the “male hormone.” But both men and women produce testosterone, just in different amounts. For athletes with DSD, the levels can be higher than average for female competitors but are still completely natural for their bodies.

Sports governing bodies like World Athletics argue that higher testosterone levels provide an unfair advantage in speed and endurance. As a result, DSD athletes are required to lower their natural hormone levels—often through medication—if they want to compete in certain events, especially middle-distance running.

However, many critics question whether punishing an athlete for their natural biology is justified. Plenty of champions, like swimmer Michael Phelps, have physical traits that give them an edge (in Phelps’s case, his wingspan and an unusually low production of lactic acid). But his natural advantages are celebrated rather than regulated. So the argument against this is why women with higher testosterone levels are asked to medically alter themselves just to compete.

DSD Regulations and Their Impact on African Athletes

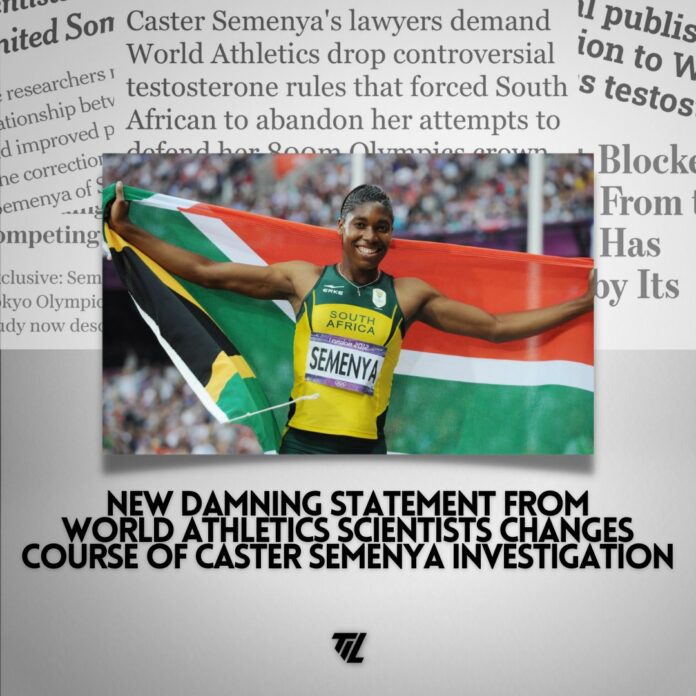

African athletes like Caster Semenya, Francine Niyonsaba, Christine Mboma, Beatrice Masilingi and Imane Khelif have become the face of the DSD debate, not necessarily by choice, but because the regulations disproportionately affect them.

Caster Semenya, a two-time Olympic champion in the 800m, has been forced out of her preferred event due to the regulations. Despite her dominance on the track, she has been barred unless she undergoes medical treatment to reduce her natural testosterone levels.

Semanya is by far the most famous case especially as she has taken her legal battle against the regulations to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). In a significant win, the court recognized that her rights had been violated when Swiss authorities failed to properly protect her. Although this ruling doesn’t automatically change World Athletics’ policies, it’s a major step toward calling out the potential discrimination in these rules.

Semanya – Legal Battle Timeline

CAS, Swiss Courts, and the ECHR

| 1. IAAF/World Athletics Regulationso In 2018, the organization introduced DSD regulations that set a cap at 5 nmol/L of testosterone for certain women’s events (400m to 1500m).

o Athletes like Semenya had to suppress their testosterone (through medication or other interventions) for six months prior to competing. 2. Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) o Semenya challenged these rules, and even though CAS acknowledged they were discriminatory, it upheld them as “necessary, reasonable, and proportionate” to maintain a level playing field. 3. Swiss Federal Tribunal (SFT) o On appeal, the Swiss Federal Tribunal supported CAS’s decision, rejecting Semenya’s argument that the regulations violated public policy. 4. European Court of Human Rights (ECHR)

|

Francine Niyonsaba, unable to compete in the 800m, transitioned to longer-distance events such as the 5000m and 10,000m where she is simply not the same dominant force. Unlike Semanya, she agreed to move to longer distances in order to save her career, leaving the middle distances where she is more naturally suited to.

Christine Mboma and Beatrice Masilingi were deemed ineligible for the 400m at the Tokyo Olympics but adapted to compete in the 200m event, where Mboma won silver.

These cases highlight how African athletes, particularly those from rural or economically disadvantaged backgrounds, are left with limited options: comply with medical interventions, shift events, or leave the sport altogether.

The racial dimension cannot be ignored. The vast majority of athletes affected by these rules are women from Africa, leading to accusations that DSD regulations disproportionately police the bodies of African women. If these rules were truly about testosterone and performance, why are only certain events restricted? Why do they not apply to all sporting disciplines equally?

These rules have not only applied to athletics as we all saw during the last Olympics in the case of Algerian boxer, Imane Khelif who became the subject of online abuse and unfair commentary as she coasted to a gold medal. Her case at the Olympics was not helped by the fact that in 2024, she was disqualified from the Women’s World Boxing Championships due to eligibility concerns regarding her sex characteristics. This decision mirrored similar exclusions in athletics and swimming.

A Battle Over Fairness or a Battle Over Control?

Proponents of the regulations argue that competitive fairness is at stake. They cite studies suggesting that elevated testosterone levels contribute to advantages in muscle mass, oxygen uptake, and recovery rates. However, critics challenge this claim on multiple grounds:

- Scientific Uncertainty: Studies on testosterone’s effect on performance remain inconclusive. Some research suggests that while testosterone influences muscle growth, its effect on performance varies between individuals.

- Ethical Considerations: Forcing athletes to alter their natural hormone levels raises serious ethical concerns. Medical interventions should be a choice, not a requirement for participation.

- Gender and Racial Bias: These regulations disproportionately affect non-Western athletes, particularly African women, reinforcing a history of racial and gender policing in sports.

Here, there’s a two-way street: on one side, sports organizations argue that higher testosterone gives an unfair advantage in events reliant on speed, strength, or endurance. On the other, critics point out that all elite athletes have exceptional traits. Swimmer Michael Phelps’s unusual wingspan and lower lactic acid production make him a once-in-a-generation champion—yet no one has ever asked him to alter his body chemistry.

For hyperandrogenic athletes, however, sports federations like World Athletics require them to medically suppress their testosterone levels to be eligible for the women’s category. Critics say this essentially punishes them for their natural biology, and this raises serious ethical and human rights concerns.

Conclusion: The Road Ahead for African Athletes

DSD regulations have reshaped the landscape of international athletics, with African athletes bearing the brunt of exclusionary policies. If fairness is truly the goal, sports organizations must reconsider whether their definitions of sex and gender promote inclusivity or merely reinforce systemic bias.

The ongoing battle over DSD regulations and transgender participation illustrates that sports governance is at a crossroads. While organizations prioritize the protection of women’s categories, they risk reinforcing social biases about who counts as a “real” woman. Athletes like Caster Semenya bear the brunt of these decisions, subjected to invasive testing and forced to fight lengthy legal battles.

In a world that celebrates athletes for pushing the limits of human performance, it’s worth asking why some extraordinary physical traits are hailed as heroic while others are regulated out of existence. The question is less about the science of testosterone than about who gets to define womanhood—and whether sports can uphold fundamental human rights while preserving fair competition.

The choice facing international sports is not just about testosterone levels; it is about the fundamental values that govern competition. Should sport be about natural ability, or should it be about conformity to strict biological classifications? Should athletes be celebrated for their talent, or should they be scrutinized for their biology?

Until these questions are answered, African athletes like Caster Semenya, Francine Niyonsaba, Imane Khelif, Christine Mboma, and others will remain symbols of a larger struggle—one that goes beyond sports and into the very nature of identity, fairness, and human rights. For now, it does seem like international organizations have taken a stand. International sports organizations have further tightened their stance; World Athletics for example, have even further lowered the allowed testosterone levels, the time frames for lowering same and have tightened regulations which prevent athletes from challenging these regulations in court as they must now sign to be bound by these rules before they compete. However, the debate continues.